What constitutes enough?

What constitutes enough?

The actuarial shortcut of ‘20 years in retirement’ is dated. If you’re 40 today, you can reasonably expect to live 15–20 years longer than your parents.

The actuarial shortcut of ‘20 years in retirement’ is dated. If you’re 40 today, you can reasonably expect to live 15–20 years longer than your parents.

That potentially doubles your retirement duration from two decades to four… without a matching extension to your working life. Even if retirement ages haven’t changed much, the old replacement‑ratio heuristics needs upgrading, or you risk a long, underfunded victory lap. ‘Enough’ shouldn’t be measured as a capital amount, but rather as a sustainable cashflow.

Our discipline here is to model retirement in phases – go‑go, slow‑go, and then no‑go, stress‑testing

expenses, markets, and inflation through each of these. GTC uses a rules‑based review process in this regard, leaning heavily on in‑house tools like TrueNorth to keep assumptions honest and portfolios aligned to mandate. The output you need is not a single ‘number’ but a range of sustainable, inflation‑linked incomes under good‑case and bad‑case scenarios.

Don’t anchor on a round capital figure (as ‘braai-planning’ often does). Anchor on what income your capital can safely produce – after tax and after medical‑inflation drift. We strongly advocate planning for what’s probable, hedging out what’s possible.

Politics & policy

The ANC‑led landscape now includes a Government of National Unity (GNU); there’s more coalition choreography, more policy uncertainty – and occasionally more pragmatism than social media allows. Markets respond to credible fiscal frames and grown‑up engagement, which we have seen at points in 2025, even amid noise.

Differential municipal performance is a real planning variable; it affects security costs, water/energy contingencies, property valuations, and even insurance excesses. Investors are voting with moving vans. The perception – often with data behind it – is that DA‑run metros are better managed. Result: semigration has pulled demand, wealth and prices coastward. Yet higher Cape valuations, tight yields and tourism dynamics change the maths for retirees trying to swap like‑for‑like homes from Johannesburg or Pretoria.

Don’t confuse a lifestyle upgrade with an investment return. If you must buy in the Cape, treat the extra capital you sink into the walls as consumption first, asset second. In many suburbs, rent‑first, decide‑later is the smarter on‑ramp; gross yields near 8% can net to <5% once levies, rates and maintenance are counted – often below a balanced portfolio’s expected real return.

Currency common sense: Hedge the rand, don’t abandon it

We all know the script: ‘the rand only falls; go offshore at any price.’ Reality is loopier. The USD/ZAR whipsaws in both directions; 2024’s last quarter saw the dollar surge against the rand, then Q1‑2025 gave back some ground. Translation: timing‑by‑headline can hurt, and a disciplined, diversified currency mix matters more than brave calls at cocktail hour.

An all‑offshore portfolio can be as risky (and tax‑inefficient) as an all‑local one. Match rand liabilities (local living costs) with enough rand assets to damp currency pain, then own sufficient hard‑currency growth for structural hedge and opportunity. Rebalance methodically; don’t chase yesterday’s move.

Growth still pays the bills (even if your nerves prefer cash)

In a previous Trendline article ‘Retirement reality check’, we cautioned that many investors are too conservative for too long – a risk in itself when medical inflation outruns cash returns. Markets zig and zag (and occasionally jitterbug), but over decades, equities and real assets are the engines that keep purchasing power intact.

We implement this with an ‘and/or’ mindset – using passive building blocks where markets are efficient and active managers where there’s alpha to earn and risks to mitigate. Add real assets judiciously: gold can diversify tail risks but remember it doesn’t pay an income and is best expressed via well‑researched structures or quality miners. As for the allure of non‑yielding alternatives (art, cars, crypto), we’ve said it before: treat these as interesting spice, not the main meal.

Contrarian take: Owning some gold doesn’t make you a doomsayer; ignoring its role as a non‑correlated diversifier can make you an avoidable hostage to equity cycles.

Income architecture: Get the annuity decision right

(and review it)

At different stages of your retirement you’ll progressively convert capital into income. Living annuities, life (guaranteed) annuities, and hybrid annuities are conventional conversion products. Living annuities give you flexibility (you choose the drawdown; 2.5–17.5% is the regulatory band), but you carry sequence‑of‑returns and longevity risk. Life annuities offload longevity risk to the insurer (income for life; increases depend on structure). Many retirees sensibly guarantee essentials with a life annuity and invest the surplus for growth via a living annuity. Professional advice here is paramount.

At different stages of your retirement you’ll progressively convert capital into income. Living annuities, life (guaranteed) annuities, and hybrid annuities are conventional conversion products. Living annuities give you flexibility (you choose the drawdown; 2.5–17.5% is the regulatory band), but you carry sequence‑of‑returns and longevity risk. Life annuities offload longevity risk to the insurer (income for life; increases depend on structure). Many retirees sensibly guarantee essentials with a life annuity and invest the surplus for growth via a living annuity. Professional advice here is paramount.

Contrarian take

A smaller guaranteed “paycheque for life” can unlock more risk capacity in your growth bucket – reducing the urge (or the necessity) to sell at market lows.

The elephant in the lounge: Family finance leakages

Two realities can quietly erode ‘enough’: The Eight‑year Rule

Budget at least eight years of post‑school support before kids are truly self‑funding. It’s sobering arithmetic: years x kids x total annual cost, compounded, is a very real detour from your retirement highway.

The bank of mom and dad (extended hours)

Funding adult children’s lifestyle costs into their mid‑twenties (or beyond) feels loving, but it’s costly in compound terms. R100k a year diverted from your retirement during prime compounding years is a large future hole – multiplied by siblings, it’s a crater.

Contrarian take

Put your own oxygen mask on first. Budget finite, clearly communicated support (with stop‑dates), and redirect savings into your plan. Your 65‑year‑old self will thank you (so will your kids, when they aren’t supporting you later).

The Two‑pot temptation: Use sparingly, not seasonally

We counselled extensively during Two‑pot’s rollout and saw a trend that worries us: members tapping retirement savings for predictable monthly expenses – DSTV, takeaways, school fees – instead of genuine emergencies. It felt easy; it is expensive in lost compounding.

We counselled extensively during Two‑pot’s rollout and saw a trend that worries us: members tapping retirement savings for predictable monthly expenses – DSTV, takeaways, school fees – instead of genuine emergencies. It felt easy; it is expensive in lost compounding.

Contrarian take

Keep a separate emergency fund and treat Two‑pot like the glass case on the wall: ‘Break only in case of fire.’ The line between ‘need’ and ‘nice‑to‑have’ is thinner than your retirement can afford.

Property: The Western Cape itch- and the numbers that scratch back

Cape price inflation has outrun Gauteng for a decade. Many semigrants find they can’t replace their old home like‑for‑like without injecting portfolio capital – concentrating risk and shrinking income‑producing assets.

Our standing guidance

If the Cape is a retirement aspiration, fine – but model the opportunity cost. Buying a smaller home and renting the dream for blocks of the year can preserve capital and increase flexibility. If you do buy, add buffers for rates, special levies and ‘borehole‑itis’.

Contrarian take

Owning one expensive, illiquid, single‑geography house is not ‘diversification’, it’s romance. Lovely, but know the price.

Pulling it together: A working definition of ‘enough’

Enough is the point at which your after‑tax, inflation‑linked income – derived from a diversified portfolio across currencies and asset classes, inside optimised tax wrappers – funds your essential lifestyle for life, with discretionary spending flexible enough to down‑shift if markets misbehave, and a clear governance process that reviews and rebalances the plan annually.

Concretely, we encourage clients to know (and revisit) these six numbers:

1. Essential monthly spend (today’s rands, then index at CPI+ for medicals).

2. Guaranteed income floor (state, employer pensions, life annuity).

3. Portfolio drawdown rate – Keep in the lower part of the living annuity limits of 2.5 – 17.5%. 4 – 5% is a common sustainable target.

4. Currency mix (rand vs hard‑currency assets matched to rand‑denominated liabilities).

5. Liquidity runway (2-3 years’ essential spend in low‑volatility assets to ride out market slumps).

6. Review cadence (annual plan reviews; mandate adherence; scenario tests).

Overlay South Africa’s realities – GNU ebb and flow, service‑delivery variance, immigration/admin surprises – and you’ve got a plan that accepts volatility without being ruled by it.

Brief, brave, contrarian notes (pin to the fridge)

Not all risk is bad. The bigger danger is too little growth for too long.

Not all risk is bad. The bigger danger is too little growth for too long.- Offshore ≠ panacea. It’s a tool, not a religion; use it deliberately and rebalance.

- Gold isn’t a payoff; it’s a policy. Small, structural allocation; review annually.

- The Cape is for hearts; spreadsheets are for heads. Sometimes rent the dream before you marry it.

- Two‑pot is not a subscription service. Treat it like a fire extinguisher, not a tap.

- Your kids are watching. Boundaries today are financial literacy tomorrow.

A word on process and partners

We believe in process over prediction – evidence, mandates, and measured manager selection. That’s how we balance passive efficiency with active conviction across cycles. An annual investment review is not just paperwork but a plan‑maintenance check – catching mandate drift, updating life events, and re‑anchoring long‑term goals.

We believe in process over prediction – evidence, mandates, and measured manager selection. That’s how we balance passive efficiency with active conviction across cycles. An annual investment review is not just paperwork but a plan‑maintenance check – catching mandate drift, updating life events, and re‑anchoring long‑term goals.

Because in the end, ‘enough’ is not a magic number. It’s the compound output of thousands of sound, sometimes boring, occasionally brave decisions – made consistently, reviewed regularly, and calibrated to your life, not your neighbour’s.

If you’re ready to turn this definition into your plan, we’re ready to do the unglamorous work that makes glamorous retirements possible.

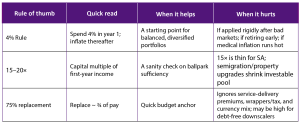

Where the ‘rules of thumb’ help (and where they mislead)

Rules like the 4% Rule, the 15–20× Rule, and the 75% Replacement Rule are useful to start a conversation about ‘enough’. They are not a finished plan. South African investors face longevity shifts, rand‑volatility, municipal/service‑delivery premiums, and property price dispersion (hello, Western Cape) that can bend these rules out of shape if applied uncritically.

Rules like the 4% Rule, the 15–20× Rule, and the 75% Replacement Rule are useful to start a conversation about ‘enough’. They are not a finished plan. South African investors face longevity shifts, rand‑volatility, municipal/service‑delivery premiums, and property price dispersion (hello, Western Cape) that can bend these rules out of shape if applied uncritically.

The 4% Rule (a.k.a. the ‘safe withdrawal rate’)

What it says: In year one of retirement, withdraw 4% of your portfolio; thereafter increase that rand amount with inflation. Historically (in US data) this survived most 30‑year periods.

Why SA investors should be cautious: It’s based on US market history (different inflation, interest-rate regimes, and tax wrappers). SA return sequences and rand swings can be harsher, and medical inflation bites harder in later life.

In living annuities, the regulatory band is 2.5-17.5%, but that’s a limit, not a target; long‑run sustainability often sits nearer 4–5% – and lower if you retire early or carry high rand‑denominated fixed costs. After a negative market year, sticking rigidly to the 4% inflation‑escalated rand amount can do real damage (sequence risk). A dynamic withdrawal that trims increases after poor returns is more robust.

GTC view: Treat 4% as a starting point for a balanced portfolio, not a promise. Pair it with a guaranteed income floor (life annuity for essentials) so your living‑annuity bucket can ride out volatility without forcing sales at bad prices. Re‑test annually with TrueNorth, not annually with hope.

The 15-20× Rule (capital multiple)

What it says: Aim to retire with 15–20 times your required first‑year retirement income (or sometimes salary).

- 15× implies a 6.7% first‑year draw,

- 20× implies 5%,

- 25× (the inverse of 4%) implies 4%.

Why SA investors should be cautious:

- 15× is usually too light in SA unless you’re retiring later, carry strong guaranteed income, and can slash expenses in downturns. With longer life expectancy and spikier inflation, 20–25× is more realistic for a traditional 65‑year-old retiree seeking high probability of success.

- Large property upgrades (common for semigrants) absorb capital and lower the investable multiple; that makes 15× particularly risky if you’ve just traded up to coastal valuations and lower net rental yields.

- If essentials are partly annuitised (inflation‑linked or with‑profit life annuity), the required multiple on your remaining discretionary need can be lower – but only if you truly ring‑fence the drawdown discipline on the living‑annuity side.

GTC view: For most South Africans, our planning spine starts at ~20–25× of essential spend (after tax), higher if you retire before 65, support adult children, or expect above‑CPI medical costs. We then shrink that multiple by locking in a life‑annuity floor for groceries/levies/medical and sizing the growth bucket to your

volatility tolerance.

The 75% Replacement Rule (income replacement)

What it says: Plan to replace ~75% of your final pre‑retirement pay to keep your lifestyle intact.

Why SA investors should be cautious (and sometimes optimistic):

- It can be too low for high medical inflation, rising private security/utility workarounds, and municipal slippage – line items that many South Africans shoulder personally (inverters, water storage, armed response, special levies).

- It can be too high for debt‑free homeowners who downscale inland, or for those who relocate and rent in the Cape instead of tying up capital – especially if they shed work‑related costs and save on tax via wrappers.

- The rule ignores rand/hard‑currency mix: retirees who import lifestyle (travel, offshore family support, foreign subscriptions) need a higher hard‑currency hedge than a flat 75% implies.

GTC view: 75% is a blunt starting peg. We segment spend into essentials/important/discretionary, guarantee the first, growth‑fund the rest, and index medicals above CPI. A sea view is lovely; just don’t confuse it with an inflation hedge (romance ≠ asset class).

Quick comparison (rules vs. reality)

A South African ‘upgrade’ to the rules

Floor and flexibility: Secure essentials via a life annuity; keep flexible growth assets for the rest.

Drawdown discipline: Target ~4–5% long‑run from living annuities, with dynamic adjustments after weak years.

Capital multiple: Aim for 20–25× essential spend (higher for early retirement/heavy rand costs/medicals).

Currency reality: Hedge rand risk deliberately, not emotionally; align hard‑currency exposure to your hard‑currency spending, and rebalance methodically.

Property pragmatism: Treat Western Cape capital uplift as consumption first; consider rent‑first entries; watch net yields vs. portfolio opportunity cost.

Behaviour beats theory: Annual reviews catch mandate drift, family leakages (Bank of Mum & Dad), and Two‑pot temptations that quietly derail compounding.

Bottom line (our opinion)

- The 4% Rule is useful- if you pair it with an income floor and dynamic spending rules.

- 15× is seldom enough in South Africa; 20–25× of essential spend is a better anchor, then tailor down with annuitisation.

- The 75% Rule can be both too high and too low; use it only after you’ve priced in service‑delivery workarounds, medicals above CPI, currency realities, and your property choice.

In short: Keep the rules for fridge magnets; keep your plan for real life. And revisit it annually – because inflation, politics and the rand certainly will.