The hidden costs of delayed savings

_____________________________________________________

The implicit cost of waiting to save

As the costs of life increase at a faster rate than one’s salary might, funding an expense as and when it falls due, means that a greater component of your limited monthly income must be committed to that expense in the future. Against this backdrop, whether you’re preparing to save for retirement, for your children’s school fees, for a well-deserved holiday, or the acquisition of a new asset – the sooner one starts to save will significantly reduce the associated cost of that savings decision over time, and the mathematics backs this statement up.

For every month that you choose to spend, rather than save, it means that over and above the rand cost itself – you have actually spent time. The consequence this carries is that in order to meet your desired savings outcome, you will either need to increase the amount saved monthly over the remaining time horizon, or extend the date at which you expect to achieve the financial goal you’ve set.

The earlier one begins saving, the larger the potential impact of compounding on their investment, often resulting in a smaller amount than is necessary each month, when compared to what the actual expense may amount to when the time comes to utilize the investment. Time is of the essence, as it cannot be recouped once it has been spent.

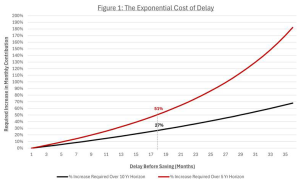

Figure One’s black line shows that if investments are returning eleven percent (11%) per year and you need to meet your financial objective in ten years’ time (10), delaying the start of your savings regime by eighteen (18) months will increase in the amount you need to save monthly by twenty seven percent (27%). If the date at which you need to draw on the investment is even nearer in the future, the monthly increase as a result of the same delay is even more significant. Figure One’s red line illustrates that were the investment horizon only five years (5), an eighteen (18) month delay results in a required increase in monthly contribution of over fifty percent (51%) to meet the obligation.

Given that markets are cyclical and that there is a myriad of factors that allow certain companies to thrive whilst others fail, might it not be better to begin the investment journey once the market has dislocated, affording your initial contributions the best opportunity to grow over time?

Bernard Buruch has famously said that ‘The main purpose of the stock market is to make fools of as many men as possible’, with this statement giving way to Warren Buffet’s ‘The only value of stock forecasters is to make fortune tellers look good’ – why might these two great minds bare such hostility towards the act of seeking the best return on one’s investment through the timing of the price one pays? Simply, it is because the short-term direction of stock prices is close to random and so time spent in the market is better than attempting to time the market in almost every scenario.

Whilst it is true that one receives better value for money after the market has fallen to its low, rather than purchasing at any other point – no one can possibly know for sure what the market will do next at any given point, and so a consistent contribution over time, allows for a time weighted average purchase price that will be somewhere in-between the lowest possible entry point and that of the highest and most undesirable. This is not a phenomenon singularly associated with developing economies like South Africa and the below indicates that the statement holds true even in the deep and very liquid capital markets of developed nations as well.

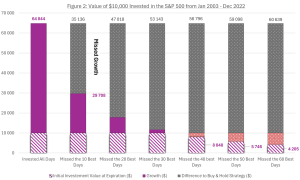

The following graph showcases the impact of ten (10) thousand Dollars invested in the SandP 500 Index from January 2003 – December 2022 and how attempting to time one’s investment exposure for the smallest fraction of time over that investment horizon causes a significantly different outcome. Adopting a buy and hold strategy for the full period has resulted in a total portfolio value at expiration of $64,844. Missing only the ten (10) best trading days in the series has resulted in a total portfolio value at expiration of $29,708 – representing a missed growth opportunity of $35,136 and ultimately a 54% reduction in portfolio value.

A more sobering realisation is that if one missed the sixty (60) best trading days in the series, their total portfolio value at expiration would have plummeted to $4,205 – representing a missed growth opportunity of $60,639 and ultimately a 94% reduction in the value that the buy and hold strategy would have returned. Most significantly to note, is that once the fourty (40) best trading days over the twenty (20) year series were missed, the growth on the initial investment actually turned negative. This is indicated by the red polka dotted areas.

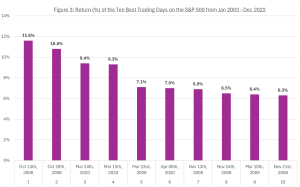

The returns in percentage terms of the ten (10) best days missed are not outrageous in isolation either, as is shown in the graph below: so why is the impact of their absence so pronounced?

This is because the best trading days often take place directly after the worst. An investor attempting to time the market, may switch out of their falling position and into a relatively safer asset class like cash and cash equivalents in an attempt to limit their losses in a falling market – whilst this action does carry with it downside protection, it locks in capital losses as well, in that the investor is no longer able to participate in the recovery of the market (whenever that may be) because they are holding cash. When they eventually do limp back in, the price at which they exited, and the price at which they re-enter are starkly contrasted – resulting in a greater cost than it would have, had they simply adopted the buy and hold strategy.

Whilst the critics might rally to dismiss the above as a one sided argument, proclaiming that it is built on too pure a misfortune to have missed the best trading days and to have only participated in the worst, consider that over the above time series – seven (7) of the ten (10) best trading days above took place when the market was ‘Bearish’. This is a term used to characterise a market when conditions are particularly uncomfortable for equity investors, and where share prices are carrying negative momentum over time.

Who then would be so bold to attempt timing their entry in that environment with conviction, had they not already held the position?

The above serves to illustrate that one should not put off their decision to save for fear that their entry could be better timed or that they might not have enough to begin the journey – simply deciding to start is the best possible outcome.

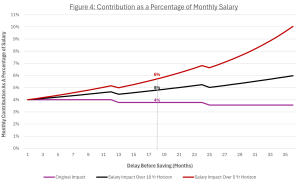

Whilst Figure One has displayed the nominal consequence of delay, and with Figures Two and Three, illustrating the cost associated with a lack of commitment to the long-term. Figure Four illustrates the impact on one’s cost of living in the future.

Figure Four indicates the elevated cost of the monthly contribution towards the investment objective as a percentage of one’s salary, whilst assuming that the salary increases year on year by an inflationary assumption of six percent (6%). The initial salary figure is R25,000 per month and the monthly contribution represents a fixed R1,000 per month which equates to four percent (4%) of the starting monthly salary. Here the cost of delay is represented in percentage terms on the salary structure, but where the percentage increases from figure One still apply.

Allowing for rounding discrepancies, the cost of the eighteen (18) month delay represented by the black line indicates a required increase of roughly twenty seven percent (27%) and the red line an increase of roughly fifty percent (51%).

What is important to take away is that through the adoption of a long-term approach to your savings regime, and where the starting figure is fixed at R1,000 – the percentage that this monthly obligation represents trends downwards over time rather than upwards as one’s salary increases, affording some respite in the present without it coming at the expense of one’s future. This is illustrated by the purple line.

The most important step in one’s financial planning exercise is choosing an investment that is appropriate, both in terms of one’s risk profile and the amount of time required to achieve the financial objective. Key information such as the investment vehicle’s time horizon and the exposure it has to growth assets must be considered, as it directly informs the volatility of the vehicle’s return profile over time. It is true that an elevated volatility profile usually accompanies portfolios with large exposures to growth assets, and so the loss of client capital is a very real risk. However, it is also true that without that risk present there can be no compounding growth, and ultimately, one’s investment objective would be underfunded at expiration were it not to be there. The best possible mitigation of potential losses – is discipline.

Simply having the fortitude to remain invested through the inevitable turbulence that an equity market produces, allows the investment to achieve its targeted outcome in all but the most extreme of cases – this creates the greatest opportunity for the power of compound interest to increase the value of your money, and for your desired investment outcome to be achieved.